We finally head to the Nine Mile Canyon petroglyphs.

National weather service predicted only a 20% chance of precipitation. (Actually, strong winds and dark clouds hit the canyon about 3:00 p.m., and we left before getting even halfway through the canyon glyphs.) We are eager knowing that scholars, who have spent years exploring the canyon, estimate that there are over 1,000 sites and 10,000 images in the canyon and side canyons.

I wondered why the 50 miles of Nine Mile Canyon were so important to the Fremont people of this area around 1,100 A.D. So I consulted a geo-physical map of Utah. It looks to me as if Nine Mile Canyon was the interstate highway of its day, and the rock art panels like highway billboards advertising human presence and good hunting.

(OK, that’s a little silly, but only a little.)

It turns out that Nine Mile Canyon is in the Tavaputs Plateau. Tavaputs stretches all the way from north of Price down too Green River City, at least 60 miles to the south, and across eastern Utah to Colorado. The elevation of the Tavaputs Plateau varies from 8,000 to 10,000 feet (Price is at 5,000 feet, like Moab). Much of what archeologists know about the Fremont culture comes from discoveries in Nine Mile Canyon.

It is a bewildering maze of canyons with no easy access anywhere. The Green River cuts through the canyons from north to south, on its way to the Colorado River (remember John Wesley Powell?). But going east-west is impossible—except for Nine Mile Canyon.

Location is everything. All the side canyons drain into Nine Mile Canyon, which in turns flows from the western portion of the plateau to the Green River. Unlike most of the other canyons, Nine Mile Canyon does not orient north-south, but east-west. Thereby, an ancient canyon traveler not only has passage through the otherwise impenetrable plateau, but also has access to the interior canyons as well. Whoever controls the canyon, controls the area.

In addition, Nine Mile Canyon provides fertile broad bottomland in its upper reaches that even attracts ranchers today. Old “ghost” ranches and cattle pens still haunt the canyon floor.

Modern ranchers still graze their cattle in open range.

(Note the solar panel on one remodeled ranch).

Thank goodness I was only traveling at 10 m.p.h. when a young calf looked at us and darted in front of the Jeep.

Teenager. We almost had a grilled side of beef.

At 7,000 feet in elevation, the canyon is too high to grow maize (not enough frost-free days). That is, modern farmers cannot grow maize there, but there is some evidence that Fremont villagers did. Scholars still do not know how. In addition, the landscape provided ideal hunting grounds and lots of places to store (that is, “hide”!) maize grown elsewhere. There are still ancient granaries located high in the cliffs where they could be defended from poachers.

It was a highway, an advertising jungle, a supermarket gathering place, and a distribution center all rolled into one canyon package.

The canyon is rugged

and has its share of strange rock formations,

that might rival tourist traps like Arches National Park with its “balancing rock.”

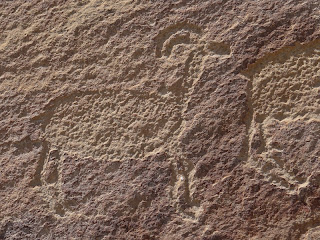

The rock art includes petroglyphs and pictographs from many cultures across centuries, indicating that the canyon was used and reused many times over. Did cultures influence each other? Fremont scholars think so. There are caves from the Barrier Canyon era.

(Note the pleasant warning marring the panel.) There are Anasazi-like figures.

(Is this mountain sheep really a left-handed batter?

I call him the Ram-bino.) Most images are clearly Fremont, both warriors

and hunters,

and clearly male. Several pictographs are like the Pilling figurines in the Price museum.

There is even art from the Ute Indians of historical times.

(The Spanish, remember, reintroduced the horse to America.)

One of my favorite panels is at the mouth of Cottonwood Canyon. It shows a variety of ancient styles but also shows the use of polychrome colors.

Scholars have determined that these pigments are not modern. The color yellow is unusual.

Even the modern graffiti is startling. This is how I sometimes sign my name!

The most famous panel in the canyon (actually it is in a side canyon—Cottonwood Canyon) is the Great Hunt Panel.

Many interpreters of rock art have used this panel to develop “universal” interpretations of the ancient purposes of rock art.

I do not think this is a productive avenue, however.

There are many mountain sheep images,

perhaps outnumbering anthropomorphic images. I find them creative and inventive in style.

My favorite is the long-necked mountain sheep (the giraffe sheep) located high on a cliff wall.

I needed a telephoto lens setting because it was impossible to get closer. The pictographic sheep looking at the camera from around the corner of a rock was pretty cool too.

There were few other animal images except for the horned (or feathered) snake.

The horned snake showed up very frequently,

often in conjunction with geometric designs.

The horned snake has important mythological significance.

Once again, many anthropomorphic figures showed strange imaginative properties.

These look like 20th century cartoon images to me, which I do not say out of disrespect.

Perhaps our modern graphic artists have themselves been influenced by the ancients. Consciously or subconsciously. One ancient artist even anticipated the DNA double-helix.

Are these places all sacred? Is there some sort of pictorial magic going on? Or do they have utilitarian purposes? Do we need to separate and distinguish?

Despite the seeming randomness and chaotic placement of images, the Fremont had a strong sense of order. Notice the concern for the use of lines, like an ancient abacus.

Puzzling “dot matrices” adorn the panels.

What I noted was how carefully each line of “dots” is lined up vertically.

I have seen this pattern repeated in many locations over many different cultures. I have yet to see any scholarly attention being given to these early mathematicians.

We will return.

Some observations:

ReplyDelete> Hash marks and dots = counting kills or observations: snakes, sheep, enemies?

> Supernatural depictions: meant to warn away 'outsiders'?

> Bug eyes = all seeing? again, to impress others with someones powers?

> Trapezoidal 'costumed' figures = tribal chiefs = 'commissioned' portraits,

depicting dominion over what else is shown nearby. Further along this line of thinking: Are the artists 'free agents', with or without a 'patron', or do they work 'on command' of their 'ruler'. This goes to asking: what was the social structure - is this known?

This raises the further broader question: is it possible to know the time span between the art? Is a whole panel executed in one lifetime, or over decades or centuries?

I suspect all of the above is possible.

ps comment:

ReplyDeleteCould the pilling figure images be commemoratives of the dead (no bodies), regardless of how they died, but perhaps heroically. Could be friend or foe.