One of the first readings I ever assigned students in a class on Native American traditions was an essay by noted anthropologist Irving Hallowell. Hallowell was studying the Ojibwe Indians of the Great Lakes region when he approached his Ojibwe informant with a skeptical question. (I am paraphrasing.)

“Is it true,” he asked, “that Indians believe that rocks speak?”

“Of course not,” was the reply. “Only some do.”

In utter futility, my students tried to elicit an explanation from me. I have been trying to puzzle out that remark ever since. (Transitors, silicon chips, crystals, etc. do not really address the issue at stake.)

Could the remark of Hallowell’s friendly informant be related somehow to ancient rock art? Were the images being created out of human imagination, or were the images there to be seen and recorded before hammer or brush were applied?

More to the point: Is it the images alone that speak to us (as our modern sensibilities would assume)? Or is it the mountains and the rocks speaking through the images? Is the landscape merely a pretty “setting” for the art? Or is it the landscape that is both beckoning and veiling itself through the images? Are human artists inventing a sacred landscape or are they responding to it, as they perceive it?

Perhaps the images are from within the rocks, not simply upon the rocks. Perhaps, as Janet suggested, some of the images are also returning back into the rocks.

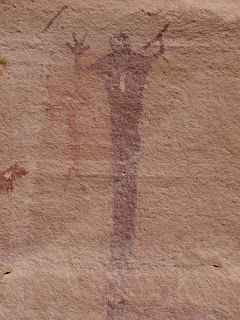

These queer thoughts were on our minds as we drove to the Buckhorn Wash Pictograph panels and stood before them. These images are in the San Rafael Swell region of central Utah and have been there since ancient times. Like Sego Canyon and the Courthouse Wash pictographs, they are Barrier Canyon images from 2,000 to 5,000 years ago.

They too have been vandalized;

but they have survived, like the juniper and pinions that grow out of barren desert rocks all around. The donations and efforts of friends and benefactors have also helped to clean up the graffiti and bullet holes.

They have allowed the ancients to confront the moderns. Buckhorn Wash is a National Historic Register site.

But we felt a bit of trepidation as well. The panels are 23.4 miles into the barren wilderness of the San Rafael region, southeast of Huntingdon.

I had read that the road down the canyon was rough and would cross Buckhorn Wash several times.

Getting lost was also a worry, since unmarked roads criss-crossed the way there. But we had a detailed National Geographic Road Map and a GPS. Not to worry.

Something else crossed my mind as I drove. I kept thinking of the old Road Runner cartoons, when Wile E. Coyote suddenly realizes that the flat, unfettered terrain he is running across drops off into a vast canyon.

Here we were driving along a flat, sandy, sage-brush-enclosed road for miles. Indeed one of the roads we travelled suddenly dropped off into the San Rafael River, 1,500 feet or so beneath us. (Of course, we knew this.) What a spectacular sight. The “Little Grand Canyon” of San Raphael was not unlike Deadhorse Point or Canyonlands in Moab, except it had more side canyons emptying into the gorge, creating a dizzying spectacle.

There are petroglyphs at the bottom of those canyons, I pointed out to Janet.

Again, the photographic dilemma of shooting pictographs in sunlight or shade presented itself. Shade gives more detail, but loses color. Sun shows color but washes out detail. We stayed around all day to do both types of shooting.

In my mind, the landscape was again crucial. Here was an intersection of canyons, forming a circular amphitheater. High above the panels was a dramatic cliff face, perfect for ritual performances.

The pictographs themselves were located at ground level on a massive marquis-like display setting.

Rock art picture books seldom show the entire panel.

They usually focus on the two “angel-like” figures,

ignoring the entire composition of figures and themes. The images all belong together.

They are not meant to be experienced as isolated images. This is a gallery of supernatural beings, and the horned serpent is the featured superstar.

Different figures are shown handling serpents

or perhaps chanting to them.

Most of the figures are life-size, but there puzzling groups of very elongated, small figures.

Again, they seem connected to the horned serpent.

Is one of the figures holding a flute, like later Kokopelli figures?

Why does another figure have a right arm and hand but a fringed appendage for a left?

And why is there a panel with 3 rows of 40 dots each, with each set of 3 dots arranged precisely vertically?

We saw similar dot patterns among the Fremont in Nine Mile Canyon. Here they show up millennia earlier.

One explanation or interpretation of rock art will clearly never be convincing. These were not made by extraterrestrials, but by people like—and unlike—us. They were canyon people.

By the way, back at the state park, a young couple from the area asked us to give them directions into the San Rafael Swell. They had never ventured there. We directed them to the “Wedge Overlook” (depicted in this blog) and to the Buckhorn Wash pictographs. They were genuinely appreciative. We were glad to do some evangelistic work in Mormon country.

Wow--that panel is HUGE!

ReplyDelete